Election Recounts and State Decentralization: The Iowa Example

The Iowa State Legislature Needs to Prioritize Recount Reform During the Upcoming Legislative Session

It was an unusually warm mid-November day when I received the phone call. Christina Bohannon, the Democratic nominee running in Iowa Congressional District 1, had requested a recount of the entire district and recount boards were being established in the counties that comprise IA-1. On the other end of the call was the Marion County Recount Board Member representing the campaign of Mariannette Miller-Meeks, the sitting Republican incumbent running for reelection in IA-1.

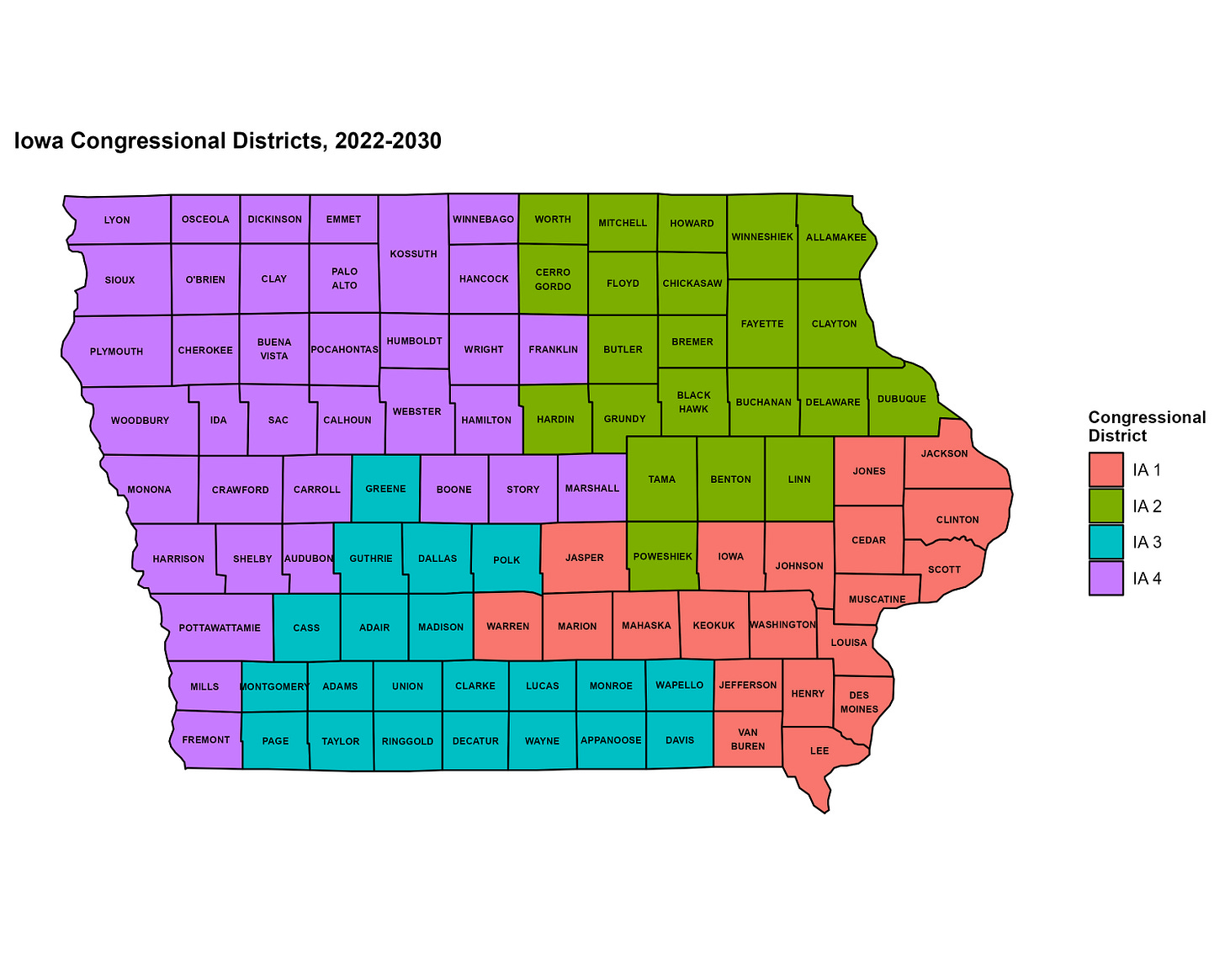

For those unfamiliar with Iowa’s political geography, IA-1 is situated in southeastern Iowa and includes the 20 counties shaded in red in the map below. The district spans from counties along the Mississippi River to the east all the way to Jasper, Marion, and Warren Counties which abut Polk County and the Des Moines metro area. While much of the district is rural in nature, the district does include two of the more urbanized counties in the state: Johnson County and Scott County.

The purpose of the call I received that warm November afternoon was to ask if I was interested and available to serve as the third, non-candidate affiliated member of the recount board. As a political science professor who studies American Politics and routinely encourages students to participate in civic and political activities, I jumped at the chance to participate in this important role.1 Over the next week or so, the planning for logistics and scheduling was finalized. The recount would begin in Marion County on Monday, November 25, 2024.

On the 25th, I made the 20 minute drive over to Knoxville from my home just west of Pella, which is across the Des Moines River and Lake Red Rock in the northeast corner of Marion County. After entering the building, I proceeded up the two central staircases to the third floor courtroom where the recount board would meet. While modernized during the pandemic, the courtroom still has its beautiful stained glass windows in the ceiling and behind the judge’s bench.

When the three board members were assembled, we were ready to start the recount. The three of us on the board unanimously agreed to a machine recount of the votes in the IA-1 race, so the Marion County Auditor and his staff were prepared to proceed with the machine recount of the more than 19,000 ballots that were cast early or on election day. After we discussed logistics, the seal on the first box of ballots was broken and the first ballots were fed through the central tabulation machine by the Auditor. When all 424 ballots from the first box were scanned, a tabulation report was printed and the board reviewed the totals from the official statement of votes cast and the tabulation report. Once that process was completed, the box was resealed and all three members of the recount board initialed the seal.

Break the seal, feed the ballots, review the reports, seal the box, repeat. This cycle repeated itself over and over again throughout the first day. When we called it a day at 7 PM on the 25th, we had nearly completed the recount for Marion County’s election-day vote. We reconvened the following morning at 8 AM to complete the election-day precinct vote and then move on to the boxes of absentee and early votes cast prior to election day.

We completed the final box of absentee ballots after 10 AM that morning, and by 11 AM, we had completed the paperwork finalizing our work as the recount board. In the end, the vote total for Rep. Miller-Meeks was confirmed (12,377) and one additional vote was added to the total for Christina Bohannon, who received 6,663 votes.

My experience on the Marion County Recount Board has further strengthened my trust in Iowa’s system of elections. Elections in the state are run by trained election officials who work diligently to implement state and federal election laws and regulations. Our interactions with the Marion County Auditor and his staff demonstrated how much they care about running elections within the county that are fair, reliable, and transparent.

Second, Iowans should trust optical scan voting. Not only are the machines tested for accuracy prior to the election, County Auditors also perform post-election audits to ensure accuracy as well. In Marion County in 2024, nearly two-thirds of the votes cast in the IA-1 race were cast at precinct locations and tabulated by a precinct tabulator. During the recount, the Auditor ran those same ballots through the County’s central tabulator and the vote totals only shifted by one vote, which should assure voters that their votes are being counted accurately.

Finally, optical scan ballots leave a “paper trail”: The ballots themselves. This affords candidates the opportunity to seek recounts in close elections to verify totals and ensure that the winner announced after the initial tabulation is indeed the winner.

That said, there is room for reform and the state legislature should act.

Not unlike most states, Iowa’s system of elections is decentralized. Iowa Code Chapter 331 designates the County Auditor as the “Commissioner of Elections” for the county, meaning that the Auditor is responsible for conducting elections within the county. Congressional races in Iowa, along with all statewide races and most state legislative races, are multi-jurisdictional elections. In other words, while the candidates in a Congressional race are seeking one single office, the voters of each jurisdiction (in this case, counties) are voting for candidates running for that office in an election conducted by the County Auditors of the counties within the district.

Under state law, recounts in Iowa for races for offices that cross county lines are also decentralized, meaning that each county establishes its own recount board to recount votes within the county. The recount boards consist of three members: (1) One member selected by the candidate who requested the recount; (2) One member selected by the winning candidate; and (3) a third member chosen by the first two members. If the first two members cannot agree on a third, the third will be appointed by the chief judge of that county’s judicial district.

Recount boards as they exist today have some discretion if machine tabulation was used to count the votes initially. Boards can choose to recount the votes using automatic tabulators or they can choose to hand count the ballots.

There are two significant issues with our current recount system. The first has to do with the size of the recount board. While a board of three members may be feasible to conduct a hand count in a small, rural county, boards of three members are not nearly large enough to recount a larger county with tens of thousands of ballots in a timely manner if a hand recount is necessary. IA-1 is illustrative of this concern. In 2024, there were less than 10,000 votes cast in a number of counties within the district. A hand recount with three recount board members would be feasible for these smaller counties. However, in Johnson County there were over 87,000 votes cast. In Scott County, there were over 90,000 votes cast. Conducting hand counts with three recount board members in the state’s largest counties within the timeframe allowed would be extremely difficult if not impossible.

Second, the decentralized nature of our recount processes is problematic for statewide, Congressional, or state legislative races. Because state code allows for each recount board to choose the method by which the votes will be recounted, it theoretically opens the door to the votes in a Congressional race being counted differently in one political jurisdiction compared to another. Using the 2024 recount of IA-1 as an example, it meant that 20 separate recount boards were appointed to re-tabulate the votes in the first Congressional district. Furthermore, it theoretically meant that some counties within the district could choose to recount using automatic tabulators while others counted each ballot by hand.

While in 2024 the recount in all 20 counties was done by automatic tabulator, this was not the case in 2020 in the IA-2 race between Miller-Meeks and Democrat Rita Hart in what was one of the closest races for a U.S. House seat in American history. In the election contest filed by Hart with the U.S. House of Representatives, Hart provided documentation of the various ways recount boards across the district recounted the votes. While several counties used only machine counting,2 other counties in the district used a hybrid approach which included the use of automatic tabulators to sort out overvotes (i.e., voter marked more than one candidate) and undervotes (i.e., voter did not mark a candidate) for hand counting to determine if the voter intended to vote for one of the two candidates.

The decentralized nature of Iowa’s recount system is problematic for Iowa voters because it sets up a scenario where the ballots of one county (or a group of counties) are evaluated in one manner and the ballots of another county (or group of counties) are evaluated in another. This non-uniform approach to recounts opens the doors to questions about voting rights and concerns about equal protection under the law.

To rectify the issues with Iowa’s decentralized recount process, the state legislature should act to standardize the recount process across Iowa’s counties. The current processes make sense for down-ballot races within a single county which have substantially fewer votes cast. For those races, one recount board is needed and that single recount board will choose a uniform approach for recounting the ballots, which minimizes questions about voting rights and concerns about equal protection. A standardized, uniform approach is needed for races that encompass multiple counties, however.

A starting point for the legislature would be the draft legislation pre-filed by Iowa Secretary of State Paul Pate prior to the last two legislative sessions. In a press release on January 6, 2023, Secretary Pate said:

The integrity of Iowa’s elections is my top priority and this bill would help ensure we have clean, secure elections and a recount process that is uniform across the state, … We’ve had the opportunity to identify these areas of improvement while observing several large-scale recounts in recent years.

In January 2024, Secretary Pate pre-filed legislation which contained multiple reforms to the recount process. It included provisions to standardize the dates for county canvassing of results, deadlines for requesting a recount, and time period in which a recount board must convene and complete its work.

Additionally, it directly addressed the issues associated with the size of the recount board and the method of recounting the votes. Regarding the former, the legislation would increase the size of the recount board according to the population of the county. The candidate requesting the recount and the winning candidate would still appoint at least one member each.

However, the appointment of the non-candidate affiliated members would change. Under the proposed legislation, the non-candidate affiliated members would be appointed by the chief judge of the county’s judicial district and must be precinct election officials. The size of the recount board would also vary by population. For counties with a population of less than 15,000, the recount board would include one non-candidate affiliated member and consist of three total members. For counties with a population of 15,000 to 49,999, the board would have two additional non-candidate affiliated members for a total of five. And for counties with populations over 50,000, the two candidates would appoint two members each and three non-candidate affiliated members would be appointed for a total of seven. By doing so, a hand recount would be much more feasible in Iowa’s larger counties.

Secretary Pate’s proposed legislation also addressed the non-uniform nature of Iowa’s recount process by standardizing the methods that recount boards can use in the process of conducting recounts. The legislation would remove the decision to use an automatic tabulator or hand count from the recount board. Instead, the candidate requesting the recount would request the method. Most importantly, if the candidate requests a hand count in one county, the candidate is required to request a hand count in all counties included in the request.

The reforms proposed by Secretary Pate would be a step in the right direction. The reforms would afford larger counties the ability to complete a hand count of ballots and at the same time would create a uniform process applied across all counties in a race that crosses county lines. Together, they would standardize the recount process and help mitigate concerns about individual voting rights and equal protection. If Secretary Pate pre-files the legislation again in January, the legislature should give serious consideration to it. If he does not pre-file it, a state legislator should move it forward in the legislative process. Regardless, the reform of our recount process should take priority during the next legislative session.

I’m interested in your comments and questions regarding this piece, so please feel free to use the comment button below to post comments and questions.

This was the second Marion County Recount Board I’ve served on. I also served on the 2020 IA-2 Marion County Recount Board as the non-affiliated third member.

The Marion County Recount Board in 2020 chose to use an automatic tabulator to complete the recount for IA-2.